|

Aircraft Wrecks in the Mountains and Deserts of the American West This Article Appeared in The

Press-Telegram

By Mark Kendall The Press-Enterprise Gary R Macha is a walking, talking black box, holding the stories of long-ago plane crashes. He rattles off the wreckage of the Aviation Age: In 1949, a pair of Hellcat fighters slams into the side of Mount Baldy during a snowstorm. No fire, but the impact kills the pilots. A mom and dad die in 1962 when their plane hits dirt nose-first near Big Bear, but their two young daughters in the back seat survive and are rescued days later. A 16-year-old girl survives for at least 54 days in snowy woods near the Oregon border after her family's plane crashes in 1967. They know because she left behind a diary of the ordeal. Macha (pronounced MOCK-uh) is one of a dozen or so serious "aviation archaeologists" in the nation who explore and document old plane crashes. He pioneered this hobby in Southern California, which has perhaps the nation's largest concentration of wrecks. "You're going back in time, traveling the past," says Macha, 53. "It does give you pause to sit back and reflect, find out why it really happened." The greatest number of crashes happened in the 1940s and 1950s. Many military pilots died in training accidents in World War II. That continued in the postwar years as heavy military activity continued in Southern California. During that time, the growing popularity of civil aviation, combined with relatively unsophisticated navigational equipment, also contributed to the high number of crashes. Bodies were removed, but the wrecks usually were left behind in remote locations. The Inland Empire's mountains and deserts hold more than their share of wrecks old and new, in part because so many flights go through the Cajon and San Gorgonio passes. More than 90 planes have crashed in the San Bernardino Mountains. In fact, Macha's explorations of old planes began in those mountains in 1963, when he was a YMCA camp counselor at Barton Flats. He happened upon a C-47B Air Force cargo plane that had hit the side of Mount San Gorgonio in a blinding snowstorm a decade earlier, killing all 13 men on board. Stunned, Macha just sat on the rock and stared at the wreckage for half an hour. That eerie find was littered with the troops' parachutes, heavy boots and winter coats. But a trail leading to the top of Mount San Gorgonio has since cut right past the crash, and the site has been picked clean of all but the metal pieces too big to pack out. Elsewhere, even the hulking plane wrecks themselves are being plucked up, in part because of the popularity of a related hobby, restoring World War II war birds. With demand rising and parts becoming more scarce, rebuilders have their eyes on wrecks. "Clandestine" types, in Macha's words, will lift them out by helicopter without the proper permits. Or wrecks will be systematically stripped, as happened a year or two ago to a rare B-17 "Flying Fortress" that crashed in the San Jacinto Mountains near Idyllwild in 1940. Others are picked apart piecemeal. Parts might wind up on the black market or sitting as souvenirs in some hiker's garage. This has led to a bit more scrutiny from some of the government agencies that either own the military planes - such as the U.S. Navy - or the land they're on. But with little supervision in the wilderness, a finders-keepers free-for-all often prevails. Paper trail Even as searches grow more sophisticated, wrecks still wait to be found. "The tougher they are to get to, the more remains," Macha says. Wreck hunting sometimes requires sifting through government records and newspaper clippings, sorting through conflicting stories and hacking through thick chaparral to get to the crash. Wrecks are left behind for a reason - they're in rugged, remote spots. A topographical map in the office of Macha's Huntington Beach home shows Southern California's mountain ranges - San Bernardino, San Gabriels, San Jacintos, Santa Anas - thick with the pinheads that mark each crash he knows of. As a high school teacher, Macha has all summer to search for new wrecks. Upon finding a plane, Macha will snap photos and typically take only the plane's data plate, which holds the serial numbers and other specifications and is prized by wreck hunters. He leaves it to the Civil Air Patrol or law enforcement to spray-paint the yellow "X" on the wreck, which means it's been found. Sorting through old wrecks might seem a bit morbid, but Macha sometimes can help people grieve long-ago losses. In many cases, families of victims had no chance to visit the crash site. Macha has retrieved artifacts for family members or even taken people to the site. So many sad stories. Macha found one private plane wreck in the Mojave Desert that had already been visited by the relatives of the dead. "I love you Dad" was spray-painted on the wreckage. Macha - who doesn't hold a pilot's license - finds lessons for aviators in the wreckage. Nearly all these disasters result from bad weather. He also finds that the most crashes, not surprisingly, come from pilots with fewer than 500 hours of flight experience. The numbers dip, then rise again with people who have logged 8,000 hours or more. He surmises it's because of age and overconfidence. These tragedies boil down to 1,400 terse entries in Macha's book "Plane Wrecks in the Mountains and Deserts of California" (Info Net Publishing. $19.95). He is working on the third edition. 'Finders-Keepers' Wreck hunters have different ideas about what should become of the wrecks they find. Some want the planes to stay as is, memorials to the dead. The more common view allows parts to be taken for legitimate restoration projects. "Aviation archaeologists" criticize people who take parts for souvenirs, though wreckhunters have been known to do that themselves. "There's always some guy who's going to go out there and just start grabbing stuff because they can," says Trey Brandt, a 30-year-old wreck hunter in Scottsdale, Ariz. He says taking little parts like gauges is OK but otherwise the plane should be left intact. "It's more or less like finders-keepers." Interpretation and enforcement of rules varies from place to place, and from government agency to government agency. For example, the U.S. Navy claims ownership of all its wrecks (and has pursued people who take them without permission) while the other branches of the service are more flexible, says Macha. Craig Fuller, a leading wreck-hunter who lives in Northern California, has mixed feelings about people taking parts or whole planes for restoration projects. While the rebuilt planes help preserve history, he says parts scavengers often rip through old wrecks with little regard for that plane's history or preserving the parts they don't need. "The majority of the recoveries are so haphazard," says Fuller, 30. "They're just in it to get cheap parts." Macha himself doesn't mind people obtaining parts or planes for legitimate rebuilding projects. Years ago, he helped pilot Steve Hinton, who runs a war bird rebuilding shop at Chino Airport, get permission to take a vertical stabilizer from one of the two Hellcats that crashed on Mount Baldy in 1949. Hinton wanted the piece for a rebuilding project. Rebuilders like Hinton, of course, want access to the wrecks, though Hinton says the crashes in Southern California have pretty much been picked bare. "Airplanes are airplanes, they're not dirt clods," says Hinton. "It is a man-made thing." Last year, Macha tried to help a friend get permission to remove the Hellcats for restoration. But the planes had been there almost 50 years, which triggers an evaluation of their historical value, and the forest service said they had to stay until that was done. However, forest service archaeologist Mike McIntyre says he expects rebuilders will eventually get the OK to remove the planes because they lack historical significance. Macha wonders how much longer the Hellcats will remain on Baldy regardless. He says they're prime for the plucking from a re-builder who doesn't want to follow the rules. But as some wrecks disappear, others still elude most wreck-hunters, including a crash just on the other side of the same mountain. A huge C-46 cargo plane hit Baldy in 1945 and slid down the deadly steep north side. Macha's agile son has made it to the wreck, but it's really not a safe trek without ropes. In the summer, if you look closely at Baldy's north side from across the mountain range in Wrightwood, you can see the mangled pile of aluminum glisten in the sun, still waiting for the yellow "X" it may never get. Mark Kendall can be reached by e-mail at mkendall@pe.com or by phone at (909) 782-7521.

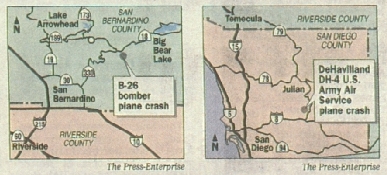

If you go Many plane wrecks are difficult to get to but the following two are easy hikes. Always bring sturdy boots and water with you into the wilderness. Don't go alone, and don't take anything at the wreckage site - except pictures. A B-26 bomber crashed into Keller Peak in the San Bernardino Mountains in 1942, and all nine men aboard died. Today the engines and landing gear struts remain on the north slope just below the top of the peak. Getting there: Take Highway 330 to Running Springs then go east on Highway 18 in the direction of Big Bear Lake, taking Keller Peak Road at the Deer Lick Station turnoff (just outside of Running Springs). Follow Keller Peak Road to the top of Keller Peak (7,882 feet) and park your vehicle. It's an easy hike - 400 yards round trip - but there is heavy undergrowth. In 1922, a DeHavilland DH-4 U.S. Army Air Service plane crashed on the south ridge and east slope of Cuyamaca Mountain in San Diego County, killing the pilot and gunner. Today, the engine, a few other parts and a monument remain. From Temecula, take Highway 79 south into San Diego County, past Julian, to Cuyamaca Rancho State Park. Park your vehicle at the Green Valley Camp and Picnic Area. then walk north of the campground to Monument Trail. Hike two miles to the junction of West Mesa Fire Road, where you will find the engine and monument. Mountain lions are common in this area, so don't go alone. |

|

|